Table of Contents

A professor once conducted an experiment where she asked students to evaluate two job candidates. Candidate A had stellar credentials. Candidate B had mediocre ones. The twist? Half the students were told Candidate A supported their political party. The other half were told Candidate A opposed it.

The results were predictable in the worst way. Students suddenly discovered flaws in Candidate A’s resume when he disagreed with them politically. Those same flaws vanished when he shared their views. These weren’t dumb people. They were studying at one of the world’s most selective universities. Yet they bent reality like taffy to fit their preferences.

This wasn’t stupidity. It was strategy.

The Game Nobody Admits They’re Playing

Think of belief as currency. Most people assume we trade this currency for truth. We gather evidence, weigh options, and purchase the most accurate worldview our cognitive budget allows. This model makes sense. It’s also wrong.

Beliefs buy other things too. They purchase membership in tribes. They acquire status. They maintain friendships. They signal loyalty. Sometimes these prizes cost more than truth but deliver better returns.

Game theory reveals the hidden math. When you’re deciding what to believe, you’re not just asking “what’s true?” You’re asking “what happens if people think this is what I believe?” The second question often outweighs the first.

A scientist who discovers evidence against climate change faces a choice. She can publish it and become a pariah in her field, lose funding, and get labeled a denier. Or she can file it away and keep her career intact. The evidence doesn’t change based on her choice. But her incentives do.

She’s playing a game where truth is only one of many payoffs.

The Betting Man’s Paradox

Imagine a betting market on whether vaccines cause autism. The scientific evidence overwhelmingly says no. Yet someone places a massive bet saying yes. You might think this person is irrational.

But what if this person runs an antivaccine website that generates millions in revenue? What if their entire social circle, income stream, and identity revolve around this belief? Suddenly, the “stupid” bet makes strategic sense. They’ve calculated that the social, financial, and psychological costs of changing their mind exceed any gains from being correct.

This is the core insight of rational irrationality. People can choose false beliefs the same way chess players choose gambits. The move looks crazy until you see three steps ahead.

The mathematician John Nash proved that in strategic situations, players often choose actions that seem suboptimal in isolation but make perfect sense given what everyone else is doing. This Nash Equilibrium applies to beliefs too. Your “best” belief depends on what beliefs others hold and how they’ll react to yours.

A Republican voter in a deep red district gains nothing from acknowledging climate science if it costs them every friendship and business relationship. The evidence for climate change doesn’t change. But the game they’re playing makes the “wrong” belief the rational choice given their circumstances.

The Loyalty Tax

Every group charges admission in beliefs. Want to join the club? Better adopt the club’s views on everything from tax policy to whether that dress was blue or gold.

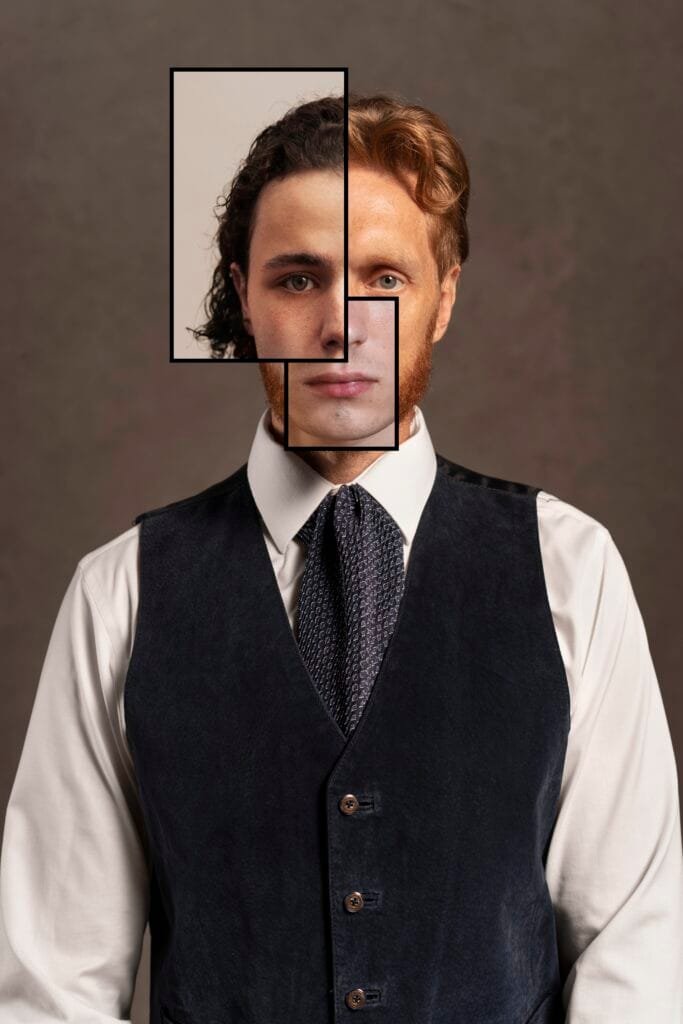

This creates a bizarre marketplace. Beliefs become loyalty tests. The more absurd the belief, the stronger the signal. If someone will believe the obviously false to stay in the group, they’ll probably stick around when things get tough.

Religious cults perfected this technique. They don’t ask members to believe small, plausible things. They demand acceptance of wild claims. This filters out the uncommitted. Only the truly devoted will swallow the bitter pill.

Political tribes use the same playbook. Each side develops signature beliefs that serve as passwords. The beliefs don’t need to be true. They need to be distinctive. They need to separate us from them.

A smart person surveying this landscape faces a choice. They can maximize truth and minimize belonging. Or they can trade some truth for a seat at the table. Game theory suggests many will take the trade.

The payoff matrix looks something like this. Hold true beliefs that contradict your tribe: lose friends, status, and opportunities. Hold false beliefs that align with your tribe: gain community, career advancement, and psychological comfort. The math isn’t pretty, but it’s math.

Sometimes beliefs act like meeting points. Their truth value matters less than their ability to coordinate behavior.

Take tipping in restaurants. Most people believe they tip to reward good service. People tip because everyone else tips and failing to tip marks you as an outsider. The belief that tipping rewards service coordinates a massive social practice. Abandoning this belief, even if you’re right, makes you the jerk who stiffs waiters. The true belief costs you. The false belief pays dividends in social acceptance.

Economic bubbles work the same way. During the housing bubble, many smart people knew prices would crash. But they also knew they’d lose their jobs if they sat out the market while competitors got rich. The person who says “the emperor has no clothes” gets exiled before the coronation ends.

Being first to truth means being first to punishment. Being wrong with everyone else means safety in numbers. Natural selection in the marketplace of ideas doesn’t reward accuracy. It rewards survival. Sometimes the survivors are the ones who believed the lie longest.

The Information Cascade

Picture a line of people choosing between two restaurants. The first person picks randomly. The second person sees this and follows. The third person does the same. By the time the tenth person arrives, everyone’s at Restaurant A even though Restaurant B might serve better food.

Each person in line acts rationally based on available information. But the collective outcome is irrational. The crowd ended up somewhere potentially worse than if everyone had chosen independently.

Beliefs cascade the same way. The first person adopts a view. Others see this and update their priors. More people jump on board. Eventually you have a stampede based on a sample size of one.

Smart people caught in these cascades face a dilemma. They can trust their own analysis or defer to the crowd. Game theory says deferring often makes sense. If a thousand people believe something, contradicting them requires extraordinary confidence. Even if you’re right, being the lone dissenter is socially costly and potentially career ending.

The rational move is to mouth the party line publicly while harboring private doubts. This creates a strange world where nobody believes the official story but everyone acts as if they do. The emperor’s nudity becomes an open secret that nobody can acknowledge without becoming a target.

The Costly Signal

Peacocks drag around absurd tails. These tails make terrible sense from a survival perspective. They’re heavy, bright, and attract predators. But they make perfect sense as signals. Only a healthy peacock can afford such an expensive ornament.

False beliefs work the same way. Adopting them demonstrates commitment precisely because they’re costly. A person who believes something obviously false for their group has proven loyalty beyond doubt. This explains why movements often rally around the least defensible claims. The claim’s weakness is the point. Believing it requires sacrifice. That sacrifice proves devotion.

A corporate executive who publicly praises the CEO’s terrible strategy signals loyalty more strongly than one who praises a good strategy. Anyone might recognize good strategy. Only a true believer will champion the indefensible.

The game theory is elegant. Groups need ways to identify commitment. Cheap signals don’t work because anyone can fake them. Expensive signals serve as credible commitments. False beliefs can be very expensive to hold. Therefore they serve as very credible signals.

Smart people understand this game. They recognize that certain beliefs function as entrance fees. Pay the fee or stay outside. For many, the price of admission is worth paying.

Here’s the Twist

Everyone sits around a table. Everyone thinks the policy is stupid. Nobody says so because they assume everyone else supports it. The policy continues.

This isn’t a thought experiment. It’s how the Soviet Union worked for decades. Citizens privately despised the regime but publicly supported it. Each person thought they were the only secret doubter. The preference falsification became self sustaining.

Game theory explains the trap. Speaking up risks punishment. Staying quiet guarantees safety. The rational choice is silence. But when everyone makes the rational choice, the irrational outcome persists.

The first person to speak truth faces maximum danger and gains minimum support. Nobody wants to be that person. So everyone waits for someone else to go first. The wait can last generations.

Smart people navigate this by maintaining two sets of beliefs. Private beliefs that track reality. Public beliefs that track survival. The split isn’t comfortable, but comfort isn’t the goal. The goal is making it through the game alive.

The Rationality of Irrationality

Choosing false beliefs isn’t a bug in human reasoning. It’s a feature.

Evolution didn’t optimize humans for truth. It optimized for reproduction. Sometimes truth helps. Sometimes it doesn’t. A ancestor who accurately believed the tiger was dangerous but froze in fear left fewer descendants than the ancestor who irrationally believed they could outrun it and tried.

Modern life presents similar tradeoffs. The person who accurately assesses their odds in competitive markets might give up too soon. The person who irrationally believes they’ll succeed keeps trying and occasionally wins. Overconfidence is costly in individual cases but profitable in aggregate.

Groups benefit from members who believe useful fictions. Armies need soldiers who believe their cause is just. Companies need employees who believe in the mission. Movements need followers who believe victory is inevitable. These beliefs might be false, but they make the group stronger.

The Exit Problem

So why don’t people just leave the game?

Because there’s no outside. Every group has beliefs that serve as admission tickets. Every marketplace rewards some degree of preference falsification. Every social structure creates incentives to believe convenient fictions.

You can switch games, but you can’t stop playing. The academic who rejects one orthodoxy for intellectual honesty will face pressure to adopt another. The whistleblower who speaks truth to power in one organization will learn to keep quiet in the next.

This creates a meta-game. Players compete not just within games but across them. The person who develops a reputation for valuing truth above loyalty finds fewer teams willing to recruit them. The person who demonstrates flexibility in belief gets invited to more tables.

Game theory suggests the optimal strategy involves calibration, not purity. Hold true beliefs when the cost is low. Adopt false beliefs when the price is right. Switch between them as circumstances demand.

Smart people hold stupid beliefs on purpose because it works. The strategy succeeds not despite its irrationality but because of it. This doesn’t mean truth is dead or that everything is relative. Physical reality continues regardless of what anyone believes. But social reality, the world of jobs and friends and status and belonging, bends toward strategic belief.

The person reading this faces a choice. They can insist on believing only what evidence supports. This path offers intellectual integrity at the cost of social friction. Or they can play the game, adopting beliefs that serve their interests even when those beliefs don’t serve truth.

Game theory can’t tell you which path to choose. It can only show the payoffs.

Most people, if they’re honest, will recognize they already play this game. The smart money says most people will keep choosing strategic belief over accurate belief as long as the incentives push that direction. Not because they’re stupid. Because they’re smart enough to see which choice the game rewards.