The spectacular rise and fall of growth stocks over the past decade reveals a fascinating paradox at the heart of modern investing. When investors collectively chase companies trading at extreme valuations, often 20x, 50x, or even 100x revenue, they create a classic game theory problem: The Prisoner’s Dilemma of Investing. This dynamic helps explain why rational actors repeatedly find themselves trapped in unsustainable bubbles.

Game Theory Framework

In game theory, the prisoner’s dilemma describes a situation where two rational actors, acting in their own self-interest, produce a worse outcome than if they had cooperated.

In the classic scenario, two suspects are arrested and interrogated separately. Each prisoner faces a choice: betray their partner by testifying against them or remain silent and cooperate. If both remain silent, they each receive a light sentence. However, if both betray each other, they both receive moderate sentences. Alternatively, if one betrays while the other stays silent, the betrayer goes free, while the silent partner receives a harsh sentence.

| Prisoner A Testifies | Prisoner A Stays Silent | |

| Prisoner B Testified | Each Serve 2 Years | Prisoner B: Goes free Prisoner A: 3 Years |

| Prisoner B Stays Silent | Prisoner A: Goes free Prisoner B: 3 Years | Each Serve 1 Year |

The dilemma arises because, from each individual’s perspective, betrayal seems like the safer choice, regardless of the other person’s actions. However, when both prisoners think this way and betray each other, they both end up worse off than if they had cooperated. This paradox highlights the tension between individual rationality and collective benefit, with applications in financial markets where cooperation would benefit everyone, but self-interest can lead to mutually harmful outcomes.

High-multiple investing creates a strikingly similar structure. When institutional investors face a company trading at extreme valuations, they encounter a matrix of options:

- If most investors avoid the stock, those who buy early capture modest gains as the company grows into its valuation over many years. However, those who abstain avoid losses but sacrifice potential returns.

- On the other hand, if most investors buy the stock, early buyers capture explosive gains as momentum builds. Those who resist miss out on career-defining returns and risk underperforming their peers.

The individually rational decision to participate in a high-multiple rally can lead to collectively irrational outcomes. Each investor has an incentive to buy, fearing underperformance rather than overvaluation. However, when everyone follows this logic, asset prices disconnect entirely from fundamentals. In high-multiple investing, a situation often arises where many investors pile into overvalued growth stocks, despite knowing they are overvalued.

Consider the position of a portfolio manager at a mutual fund in 2020-2021, watching Zoom Video Communications. In October 2020, Zoom traded at $559 per share with over 300x earnings. The company was clearly benefiting from pandemic-driven demand that didn’t feel like gravity existed.

The manager faces these calculations:

- Buy the stock. If you bought at the ‘obvious’ overvaluation point, you still had time to exit profitably. If it crashed, you lost alongside everyone else. No career risk.

- Avoid the stock. Zoom was a top holding in the ARK Innovation ETF (ARKK), which gained 153% in 2020. Managers who avoided these stocks drastically underperformed. By the time Zoom returned to fundamentals, those managers may have already been fired for 2020-2021 underperformance.

This can be showcased in this matrix:

| Investor A Participates | Investor A Avoid (Stay Rational) | |

| Investor B Participates | Investor A: Matches benchmark, keeps job, but loses 25-50% when bubble pops Investor B: Matches benchmark, keeps job, but loses 25-50% when bubble pops | Investor A: Massive underperformance, likely fired before being proven right Investor B: Captures momentum gains, outperforms dramatically |

| Investor B Avoid (Stay Rational) | Investor A: Captures momentum gains, outperforms dramatically Investor B: Massive underperformance, likely fired before being proven right | Investor A: Preserves capital, avoids crash, proven right eventually Investor B: Preserves capital, avoids crash, proven right eventually |

Even though both investors avoiding the bubble (bottom-right) produces the best collective outcome, it’s not a stable equilibrium.

In 2020-2021, fund managers who avoided stocks like Zoom, Peloton, or Tesla at extreme valuations massively underperformed and risked their careers. However, they were eventually proven right when these stocks fell in 2022. This situation highlights the concept of individual rationality (protecting your career by buying) leading to collective irrationality (market bubbles). Game theory explains why smart people do things they know are foolish.

The prisoner’s dilemma intensifies when we consider the principal-agent relationships within institutional investing. Portfolio managers, acting as agents, make decisions on behalf of investors, or principals. However, their incentive structures may not align, creating a conflict of interest.

Managers are evaluated quarterly or annually, creating pressure to chase performance even in overvalued markets. This pressure can lead to underperformance for a year or two, potentially ending a career even if the long-term thesis proves correct. Furthermore, many managers are evaluated against indexes increasingly dominated by high-multiple growth stocks. This can create tracking error and career risk, even if avoiding these stocks is the right investment decision.

The “No One Gets Fired for Buying IBM” effect is evident in today’s market. Unlike in the past, owning the same overvalued growth stocks as everyone else doesn’t lead to job loss. This is because contrarian positions require justification, while consensus positions don’t.

Game theory also sheds light on how herd behaviour emphasises the prisoner’s dilemma in high-multiple investing. This occurs when individuals observe others’ actions and follow suit, disregarding their own private information.

Imagine the following sequence:

- A respected investor announces a large position in a high-multiple growth stock

- Other investors, uncertain about their own analysis, interpret this as a positive signal

- They buy the stock, which rises, seemingly validating the initial purchase

- More investors observe the rising price and follow suit

- Eventually, almost no weight is placed on private information; everyone simply follows the herd

This transforms the game. Even investors who privately believe valuations are extreme face a coordination problem. If everyone else is buying based on observed actions rather than fundamentals, the rational response may be to join them. You’re no longer playing against reality; you’re playing against other players’ perceptions of what others will do.

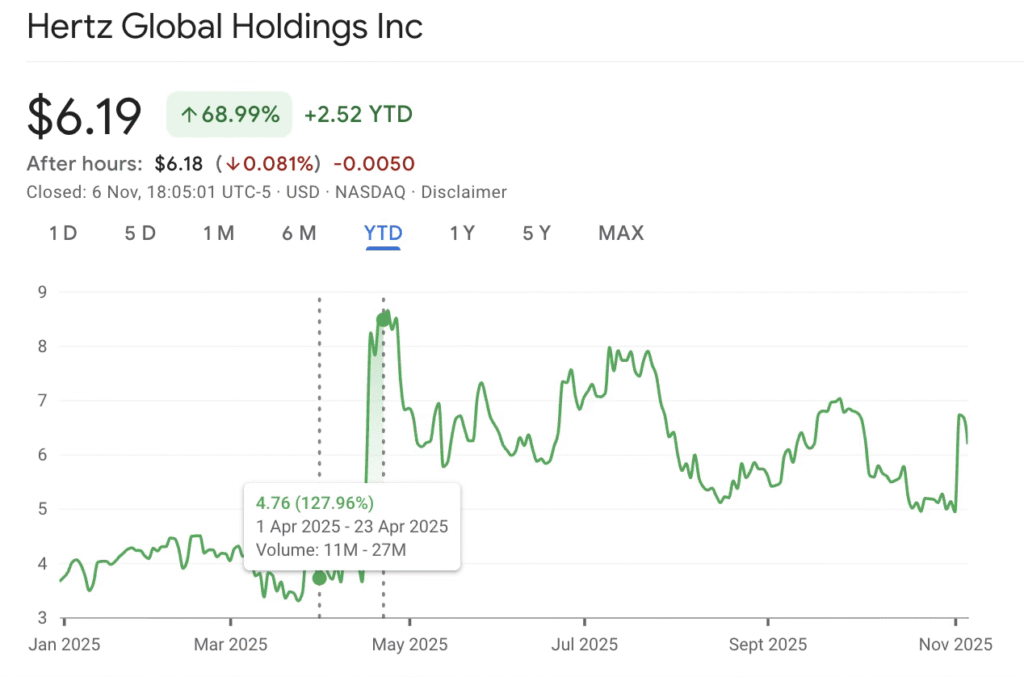

It doesn’t only apply to institutional players but all financial market players. For example, Bill Ackman confirms investing in Hertz. After the news, the value of the company doubles in just three weeks.

The game theory of high-multiple investing also has systemic implications. When enough capital flows into overvalued stocks, it creates economy-wide distortions. Companies with mediocre unit economics can raise billions at high valuations, while sustainable businesses with lower growth rates struggle to attract capital.

Carvana. Peak: $360 (August 2021) this online car dealer nearly went bankrupt; loses 99% of peak value.

Nikola. The electric truck company in June 2020 briefly achieved a $30 billion market cap same as Ford despite having no factory and no sales.

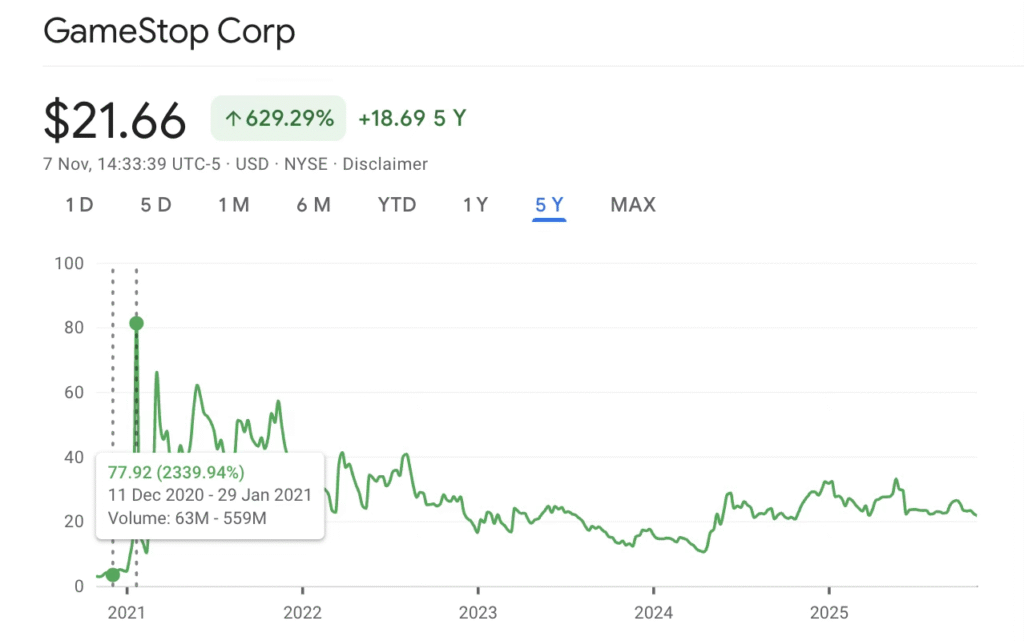

GameStop. Rose nearly 2,350% in one month in January 2021, driven by Reddit’s WallStreetBets coordinating against short sellers. Market cap briefly touched $23 billion for a declining video game retailer. This was explicit coordination to force a short squeeze, game theory made visible.

AMC Entertainment. The struggling theatre chain became a meme stock, rising nearly 500% in May-June 2021, giving it a market cap exceeding $26 billion despite bankruptcy concerns and a decline in theatre attendance. The stock price was divorced entirely from fundamentals; it was pure game theory and coordination.

Let’s say there are two examples of fund managers being rational and deciding not to follow the market, and the ones that follow that market but geared up.

Michael Burry, famous for predicting the 2008 crisis, shorted Tesla in 2020-2021 at what seemed like extreme valuations exposing 534 million dollars of value in 2021 as reported by CNBC in May. He was eventually right but the interim pain was severe due to momentum as Tesla continued rising.

No individual investor can improve their position by unilaterally selling when everyone else is buying, even if they believe valuations are unsustainable. The career risk of being wrong early overwhelms the investment risk of participating in a bubble.

There is another example that instead of being against the sentiment, tried to ride it. Think of Archegos Capital Management in March 2021. This family office used extreme leverage to build massive positions in high-multiple stocks like ViacomCBS, Discovery, and others. Archegos Capital Management turned a $1.5 billion portfolio and pumped it up into a $35 billion portfolio but then they lost $20 billion in two days. “Regular market participants and even the companies themselves were duped into thinking the price increases were caused by normal supply and demand when they were actually the artificial result.”

From this perspective, the high-multiple investing game resembles a prisoner’s dilemma where individually rational actions degrade market efficiency and economic dynamism. It’s not American and not financial, but a human exuberance problem.

1634-1637: Dutch Tulip Mania – the first known financial bubble occurred in the Netherlands when speculation drove tulip bulb prices to extreme levels where “a single bulb of tulip cost as much as 4,000 to even 5,500 florins – which meant that the best of tulips cost more than $750,000 in today’s money.”

In February 1637, the exuberance ended in Haarlem because tulip bulbs received no bids, neither initially nor at lowered prices that eventually stopped once plentiful liquidity provided by outside speculators. The insane valuations ended, and commodities entered into a fire sale, losing up to 95% of their inflated value.

1720, South Sea Bubble. Perhaps the first Ponzi scheme in history. Granted, it was created to increase profits in British trade in South America with Spanish and Portuguese. With government endorsement, where the ruling monarch becomes the ‘CEO’ of the South Sea Company creates perceived safety. If the British government backed it, how could it fail? Even Sir Isaac Newton famously lost money in this bubble, assumedly 3 million pounds in today’s value demonstrating how intellectual brilliance offers no immunity to crowd psychology.

The longer prices rose, the more ‘proof’ there seemed to be that sceptics were wrong. Those who sold early and watched prices continue rising experienced painful regret, teaching others not to exit prematurely. This created a trap where everyone waited for the ‘top’ but no one could identify it until it crashed. Share price rose from 128 in January 1720 to more than 1,000 pounds in August of the same year. By September 1720, the share was worth back to 124.

Bubbles typically last much longer than people think; they’re never less than a year in duration and usually about six years. Additionally, the way down is faster than the way up, with bubbles bursting in well under half the time it took them to inflate.

Each iteration features the same game theory: investors know valuations are extreme but rationally participate because the cost of being wrong early exceeds the cost of being wrong with everyone else. What’s perhaps most striking is that despite repeated cycles, the game never truly changes. New narratives create fresh permission structures to participate exuberantly. The prisoner’s dilemma of high-multiple investing reveals an uncomfortable truth: markets can persistently misprice assets even when participants understand the mispricing.

The growth-at-any-price phenomenon isn’t simply a story of irrational exuberance or mass delusion. It’s a rational response to a complex game with misaligned incentives, coordination problems, and asymmetric payoffs. Understanding this won’t make timing the market easier, but it might help explain why even sophisticated investors repeatedly find themselves prisoners of a dilemma they can see but cannot escape. The game continues, waiting for the next narrative to justify the next round.