Table of Contents

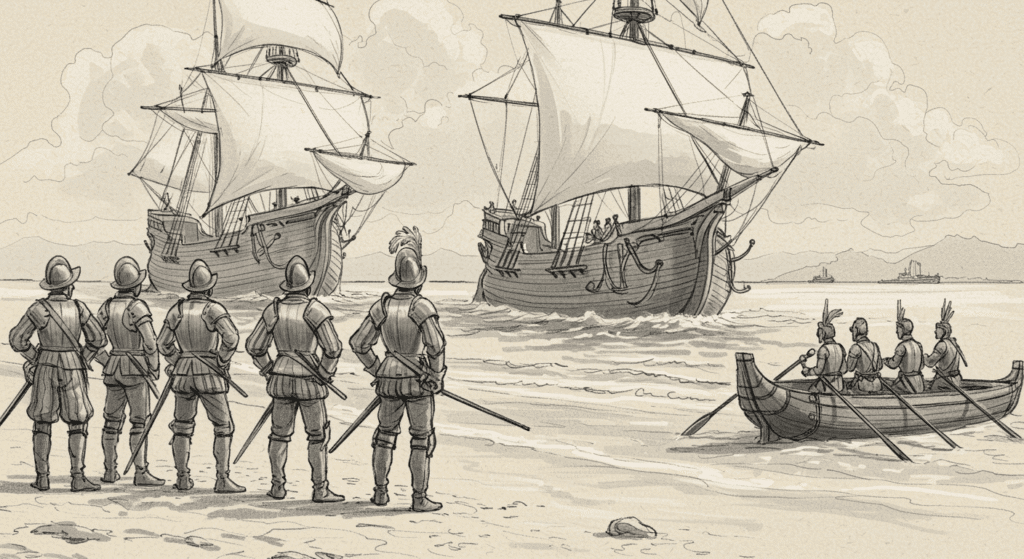

When Hernán Cortés arrived on the shores of Mexico in 1519, he made a decision that would have gotten him expelled from any modern business school. He ordered his men to burn their own ships. No escape route. No plan B. No rational exit strategy. Just eleven vessels reduced to ash and seawater while his vastly outnumbered force faced the Aztec Empire.

History remembers this as brilliant strategy. Economics textbooks call it a commitment device. Most people would call it insane.

Yet this contradiction reveals something profound about human decision making. Sometimes the path to victory requires deliberately destroying your own options. Sometimes strength comes from making yourself weak. Sometimes the smartest move is to tie your own hands.

This is the counterintuitive world of commitment devices, where game theory meets psychology and produces results that sound backwards until you see them work.

The Paradox of Power Through Weakness

A commitment device is any mechanism that restricts your future choices to change how others behave now. Think of it as strategic self-sabotage. You voluntarily limit your freedom to gain an advantage in a game you’re playing with other people, with your future self, or with circumstances.

The concept seems absurd at first glance. Why would anyone want fewer options? Every economics class teaches that more choices equal more utility. More doors mean more opportunities. More flexibility means more power to adapt.

But game theory reveals a different truth. In strategic situations, the ability to commit to a course of action can be more valuable than the freedom to choose. When your opponent knows you cannot back down, they must adjust their strategy accordingly. When you cannot change course, you force the world to navigate around you instead.

Consider the classic game of chicken. Two drivers race toward each other. The first to swerve loses. The one who holds steady wins but only if the other swerves. If neither swerves, both crash. Game theory suggests a winning strategy: visibly throw your steering wheel out the window. Once your opponent sees you cannot swerve, they must. You win by eliminating your own ability to make the rational choice.

This logic appears throughout human interaction. Labor unions gain negotiating power by authorizing strikes they would rather avoid. Generals win battles by cutting off retreat routes. Parents gain credibility with children by creating consequences they must follow through on. Nations deter attacks by building automatic retaliation systems they cannot override.

The pattern repeats endlessly. Victory through voluntary vulnerability.

The Ancient Wisdom of Binding Yourself

Homer understood commitment devices three thousand years ago. In the Odyssey, Ulysses faces the Sirens, creatures whose songs drive sailors mad with desire, luring them to crash on rocks. Ulysses knows he will want to steer toward them. He knows his future self cannot be trusted. His solution? He orders his crew to tie him to the mast and plug their own ears with wax. He transforms himself from captain to captive.

When the songs begin, Ulysses screams and begs to be released. His crew, unable to hear his pleas, row steadily past. The commitment device works perfectly. Ulysses gets to hear the legendary songs and survive, precisely because he eliminated his ability to choose.

This story captures the essence of commitment devices in strategic situations with your future self. Your present self makes a binding choice that your future self cannot undo, even when that future self desperately wants to. The restriction creates the outcome both selves ultimately prefer.

People routinely make choices they later regret. They know they will make these choices. They often wish they could stop themselves. Commitment devices offer a solution.

The classic example involves money. Someone wants to save for retirement but knows they will spend extra cash if it stays accessible. The solution? Direct deposit into a retirement account with early withdrawal penalties. The penalty functions as modern ropes binding them to the financial mast. Future temptation cannot override present commitment.

When Burning Ships Makes Perfect Sense

Return to Cortés and those burning ships. Game theory illuminates why this worked. His soldiers faced a choice architecture. They could fight fiercely or retreat to the ships. As long as ships remained, retreat stayed viable. This affected their fighting intensity. It also affected how the Aztecs perceived them.

By eliminating the retreat option, Cortés changed the game completely. His soldiers would fight harder because they had no alternative. The Aztecs, seeing invaders who destroyed their own escape route, had to recalculate. These were not explorers who might leave. These were conquerors who would stay or die.

The burning ships served as a costly signal. Anyone can claim they will never retreat. Talk is cheap. Destroying your fleet is expensive. Only someone truly committed would pay that price. The action communicated resolve more powerfully than any words could.

This principle extends far beyond military conquest. Businesses use commitment devices constantly. A company announces it will release a product by a specific date. It creates credibility penalties for missing deadlines. These restrictions seem to limit flexibility, but they actually solve a coordination problem. Teams work harder knowing failure has consequences. Customers trust promises backed by penalties.

Investors use commitment devices when they structure deals. They put money in escrow. They create clawback provisions. They demand board seats. These mechanisms tie their hands, but they also change the game with entrepreneurs. Binding commitments replace vague promises.

Even personal relationships run on commitment devices. Marriage is essentially a commitment device. Two people could simply live together, maintaining maximum flexibility. Instead, they create legal and social ties that make separation costly. Why? Because the commitment itself changes behavior. It encourages investment in the relationship. It signals seriousness to family, friends, and each other.

The wedding ring is perhaps the smallest yet most powerful commitment device ever invented. A metal circle communicates unavailability to potential rivals and reassures the partner. Its value comes not from the gold but from the visible restriction it represents.

The Technology of Self-Control

Modern technology has spawned countless commitment devices for everyday problems. Apps delete social media access during work hours. Websites block entertainment sites until tasks are complete. Alarm clocks require solving math problems before they silence. Smart thermostats prevent temperature changes. Digital locks seal cookie jars.

These tools address a fundamental game theory problem. People contain multiple selves competing for control. Morning self wants exercise. Evening self wants the couch. January self wants weight loss. December self wants pie. Sober self wants sobriety. Drunk self wants another drink.

Traditional economics assumes a unitary self making consistent choices. Game theory and behavioral economics recognize internal conflict. They model intertemporal choice as a game between different temporal selves. Commitment devices let one self win by changing the rules.

The genius of commitment devices lies in asymmetric information and power. Present self has full information about future self’s weaknesses. Present self also controls the current environment. It can create constraints that bind future self. Future self, when it arrives, operates within those constraints.

This dynamic explains the entire diet industry. People pay money to restrict their own food choices. They buy meal plans with no flexibility. They join programs with weigh-ins and public accountability. They even undergo surgery to physically limit stomach capacity. Each method works as a commitment device, using present determination to override future weakness.

When Commitment Devices Backfire

The dark side of commitment devices emerges when circumstances change unexpectedly. The same inflexibility that creates advantage in stable situations creates disaster when conditions shift.

Cortés burned his ships in 1519. This worked because he correctly assessed the situation. But imagine if a massive Aztec fleet had appeared the next day. Suddenly, the burned ships transform from strategic brilliance to catastrophic error. The commitment device becomes a death sentence.

This vulnerability explains why commitment devices work best in predictable environments. Labor unions can strike effectively when demand for their labor is stable. If the company can easily replace them, the commitment becomes leverage for management instead. Nations can commit to automatic retaliation when they trust their detection systems. False alarms could trigger nuclear war.

Modern examples abound. Companies commit to fixed-price contracts and then face unexpected cost increases. They lose money on every sale but cannot exit. Governments pass constitutional restrictions on spending and then face emergencies requiring funds. The commitment that seemed wise in good times creates catastrophe in bad times.

Personal commitment devices fail similarly. Someone commits to never eating dessert, then attends a wedding where refusing cake insults the hosts. The rigid rule creates social damage. Someone locks away their credit cards, then faces an emergency requiring immediate payment. The commitment device that prevented impulse purchases also prevents necessary spending.

This reveals a crucial insight. Commitment devices trade flexibility for credibility. Sometimes credibility is worth more than flexibility. Sometimes it is not. The art lies in knowing which situations are which.

The Credibility Game

Game theorists distinguish between cheap talk and costly signals. Anyone can say anything. Words are free. But actions that impose real costs reveal true intentions. Commitment devices function as costly signals.

When a nation deploys troops to a border, it signals intent more powerfully than diplomatic statements. The deployment costs money and creates risk. Only serious nations bear these costs. When a company invests billions in a new factory, it signals commitment to a market more convincingly than press releases. When an entrepreneur quits a stable job to launch a startup, the sacrifice communicates dedication more clearly than any business plan.

Each action serves as a commitment device that changes the strategic landscape. Partners, competitors, and customers update their beliefs based on costly actions rather than cheap words. The person who burns bridges, closes doors, and eliminates alternatives is demonstrating commitment through destruction.

This logic explains countless business practices. Companies give exclusive distribution rights. They sign long term contracts with suppliers. They invest in specialized equipment. Each choice limits flexibility but gains credibility. The commitment changes how others interact with them.

Politics runs on similar dynamics. Politicians make campaign promises knowing they will be held accountable. They go on record with positions they cannot easily reverse. They build coalitions that depend on specific commitments. The restrictions they create become sources of power.

But credibility has costs. A reputation for following through on commitments requires actually following through even when it hurts. The commitment device only works if people believe you cannot or will not override it. This creates a trap. You must sometimes make choices you would rather avoid, simply to maintain the credibility of your commitments.

Designing Your Own Constraints

Understanding commitment devices enables better decision making across domains. The key is recognizing when credible commitment creates more value than preserved flexibility.

Saving for long term goals benefits from commitment devices. Automatic transfers, locked accounts, and penalty structures all work by binding future self to present self’s priorities. The restriction creates the outcome both selves prefer.

Breaking bad habits requires commitment devices that increase the cost of undesired behavior. Make cigarettes hard to access. Delete gaming apps. Block problematic websites. Each barrier creates friction that tips the balance toward better choices.

Building good habits benefits from commitment devices that increase the cost of failing. Public accountability, financial stakes, and social commitments all raise the price of giving up. The external constraints support internal motivation.

Negotiating effectively often requires demonstrable commitment. Reveal that you have limited authority. Show that you face consequences for certain choices. Create visible costs for backing down. These constraints strengthen your position by making threats and promises credible.

Managing organizations means creating commitment devices for teams. Deadlines backed by consequences. Public roadmaps that create accountability. Incentive structures that align interests. Each mechanism binds people to desirable behaviors.

The Courage to Limit Yourself

Perhaps the deepest lesson of commitment devices is this: strength sometimes requires accepting weakness. Power sometimes flows from surrendering power. Victory sometimes demands voluntarily limiting your options.

This contradicts instinct. Every fiber screams to keep doors open, preserve flexibility, and maintain control. The commitment device asks the opposite. It demands deliberately closing doors, restricting flexibility, and surrendering control.

Yet this counterintuitive move often produces better outcomes. The person who cannot change course forces others to accommodate. The person who publicly commits mobilizes social pressure as an ally. The person who restricts future options empowers present choices.

Cortés understood this when he burned his ships. Ulysses understood when he tied himself to the mast. Modern game theory has simply formalized what strategic thinkers have always known. Sometimes you win by limiting yourself. Sometimes the best move is strategic self-sabotage.

The art lies in knowing when to bind yourself and when to stay free. When to burn the ships and when to keep them ready. When to tie yourself to the mast and when to keep your hands on the wheel.

Because commitment devices are powerful tools, but tools nonetheless. Used wisely, they transform impossible situations into victories. Used poorly, they transform reasonable positions into disasters. The difference between brilliance and folly often comes down to timing, judgment, and luck.

Which means the ultimate commitment device might be this: committing yourself to think carefully before committing yourself to anything at all.