Table of Contents

The entrepreneur sits across from investors, palms sweating, explaining why his startup will revolutionize everything. He speaks with conviction. He makes promises. He guarantees success. The investors smile politely and pass.

Three months later, they fund his competitor who said almost nothing but had quit a comfortable six figure job to sleep on a friend’s couch while building the product.

What happened? The first founder was telling. The second was signaling.

The Problem With Words

Everyone can talk. Words are cheap, sometimes literally free. When someone says they’re hardworking, trustworthy, or brilliant, what actual information does that convey? From a game theory perspective, the answer is close to zero.

Game theorists call this cheap talk. It costs nothing to produce and therefore carries no weight. The lazy person can claim to be hardworking just as easily as the actual hard worker. The dishonest person can proclaim trustworthiness with the same breath as the honest one. When anyone can make a claim regardless of whether it’s true, the claim becomes meaningless noise.

This creates what economists call a pooling equilibrium. Everyone ends up in the same pool, making the same claims, and outside observers have no reliable way to tell them apart. The marketplace of trust breaks down. Talented people get overlooked. Frauds slip through. Nobody wins except those skilled at performance art.

Enter the Signal

A signal is different from cheap talk because it’s costly. Not necessarily in money, though that can be part of it. The cost can be time, effort, risk, or opportunity. What matters is that the cost is higher for those who lack the quality they’re trying to demonstrate.

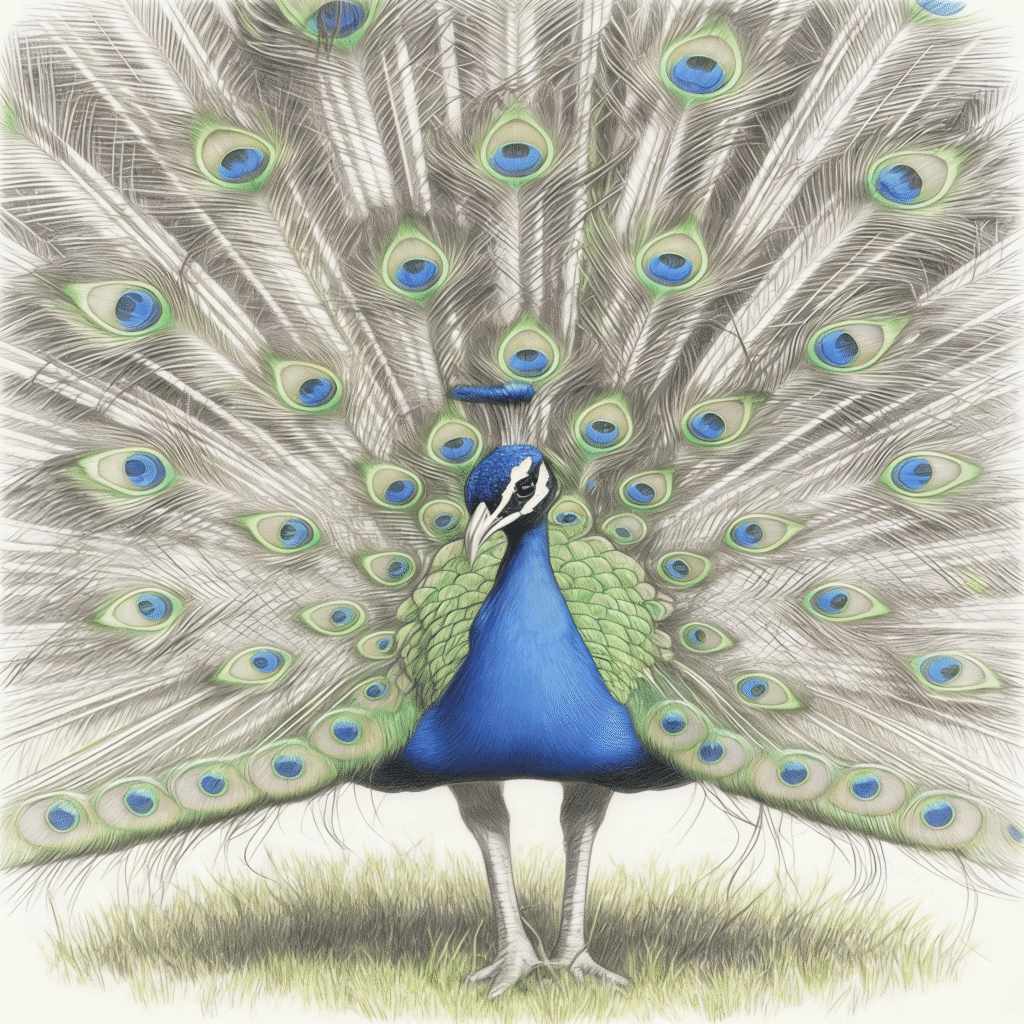

Consider the peacock’s tail. Evolution’s most absurd creation, really. Heavy, bright, cumbersome, essentially a neon sign saying “eat me” to predators. Yet peacocks with bigger tails attract more mates. Why would nature select for such an obviously stupid feature?

Because only healthy peacocks can afford to grow and maintain ridiculous tails. A sickly peacock trying to grow a massive tail would die before getting the chance to reproduce. The tail is costly, but the cost is bearable for the healthy and crushing for the weak. This makes it a reliable signal of genetic fitness.

The same logic applies to human credibility. The question becomes not what someone says, but what they’ve done that would be difficult or impossible to fake.

The Mathematics of Believability

Game theory models this through what’s called signaling games. Player one has private information about their type. Player two wants to know that information but can’t observe it directly. Player one can send a signal, but player two knows that player one might have incentive to lie.

The key insight is separation. A signal only works if different types would make different choices. If both high quality and low quality actors would send the same signal, then the signal reveals nothing.

Take education. Why do employers care about degrees? It’s not just the knowledge gained, which could theoretically be acquired through cheaper means. The degree signals something else: the ability to complete a long, often tedious process, to delay gratification, to meet deadlines, to navigate bureaucracy. These qualities predict job performance.

Someone lacking these qualities could theoretically get the degree, but the cost to them would be much higher. They might fail out. They might take twice as long. The very difficulty of obtaining the credential for those who lack the underlying qualities is what makes it valuable for those who possess them.

Cheap Talk Versus Expensive Reality

A founder can claim to be committed to their startup. That’s cheap talk. Quitting a stable job and draining savings? That’s a costly signal. The uncommitted founder would be far less willing to bear that cost.

Someone can say they believe in climate change. Free words. Installing solar panels at personal expense despite a long payback period? That’s a signal. The person who doesn’t really care won’t do it.

An executive can announce that quality matters most. Easy to say. Publicly firing the top salesperson for cutting corners? That’s credible because it hurts. The executive who doesn’t actually value quality over revenue would never make that sacrifice.

Notice the pattern. Signals involve doing something that would be irrational unless the claim were true. This is counterintuitive. We often think credibility comes from being smart and calculating. But sometimes credibility comes from appearing to make choices that only make sense if you’re being honest.

The Separation Principle

The genius of costly signals is they sort people into groups naturally. Those who can afford the cost separate themselves from those who cannot. No third party verification needed. No trust required. The mechanism is self enforcing.

A software developer could claim expertise in a programming language. Or they could contribute to open source projects in that language. The contribution is costly in time and effort, but significantly more costly for someone who lacks real skill. They would struggle, take forever, produce poor code, get rejected in code reviews. The truly skilled developer finds the cost bearable. The poser finds it prohibitive.

The market sorts itself. No one has to take anyone’s word for anything.

This explains why virtue signaling actually makes sense as a term, though not always in the way people use it. True virtue signaling involves costly demonstrations that separate the genuinely virtuous from pretenders.

Wearing a pink ribbon for breast cancer awareness isn’t a signal; it costs nothing. Organizing a fundraiser that consumes your weekends for months? That’s a signal.

The Handicap Principle

Biology reveals an even stranger truth. Sometimes the costliness itself is the point. The signal doesn’t need to convey useful information beyond “I can afford this cost.”

Arabian babblers are small birds that engage in sentinel duty. One bird perches high up, watching for predators while others forage.

Researchers thought the sentinel was helping the group. More detailed observation revealed something odd. The bird on sentinel duty was often the most dominant, well fed bird. The one who needed to forage least. The one with the least to gain from helping.

The sentinel behavior was actually a dominance display. The message: “I’m so fit that I can waste time on guard duty while you scrape for food.” Pure flex, in modern terms. Yet it conveys real information about fitness and status.

Humans do this constantly. The lawyer who works hundred hour weeks is signaling not just dedication but the capacity to endure what others cannot. The academic who writes dense, jargon filled papers inaccessible to laypeople is signaling membership in an elite club. The luxury brand that offers terrible customer service is signaling exclusivity by making access difficult.

These might seem like wasteful inefficiencies. From one angle, they are. But from a signaling perspective, the waste is the feature, not the bug. It’s what makes the signal credible.

Counter Signals and the Expert Move

Here’s where things get interesting. Once you understand signaling, you can understand counter signaling. When everyone knows you’re credible, you can afford to do things that would otherwise tank your credibility.

The billionaire can wear a T shirt and jeans. The Nobel Prize winner can explain complex ideas in simple terms. The genuinely skilled developer can admit when they don’t know something. Their credibility is already established through other costly signals. They no longer need to peacock.

This creates a strange dynamic. The person trying hardest to appear credible often appears least credible. The consultant in the expensive suit with the polished pitch deck raises more skepticism than the successful founder in sneakers. The job candidate who oversells every minor accomplishment seems more desperate than competent.

Observers pick up on these cues, often unconsciously. Trying too hard to signal suggests you lack underlying quality. Real quality doesn’t need to shout.

But here’s the trap. You can only counter signal once you’ve signaled. The billionaire earned the right to dress casually through the costly signal of building a billion dollar company. Someone without that foundation who dresses casually is just underdressed.

Skin in the Game

Nassim Taleb popularized this phrase, though the concept is ancient. Having skin in the game means you bear the costs of being wrong. It’s the ultimate credibility signal.

The financial advisor who invests their own money in what they recommend has skin in the game. The one who gets paid regardless of whether clients profit or lose does not. Who would you trust?

The CEO who accepts stock options over a higher salary has skin in the game. Their wealth rises and falls with the company. The hired gun with a guaranteed compensation package has less alignment.

The political candidate who has lived in the community for decades has skin in the game. The carpetbagger who just moved to run for office has less. One has more to lose from the community’s decline.

Skin in the game works as a signal because it aligns incentives. Someone with skin in the game doesn’t need to be trustworthy in some deep moral sense. They just need to be self interested. Their interests and yours point in the same direction. That’s often more reliable than depending on someone’s claimed good character.

The Reputation Game

Repeated interactions change the math completely. When you’ll see someone again, and again, and again, honesty becomes rational even for the dishonest.

Think of it as multiple rounds of the same game. In a single round, the used car dealer might profit from hiding defects. But if that dealer needs repeat customers and word of mouth, the short term gain gets crushed by long term losses. Reputation becomes a valuable asset. Protecting it becomes worthwhile.

This is why small towns stereotypically have more honest merchants than big cities. It’s not that small town people are inherently more ethical. It’s that they can’t escape their reputation. The market enforces honesty through repeated play.

Online marketplaces figured this out. eBay built its entire model on reputation scores. Amazon seller ratings serve the same function. The system doesn’t require anyone to be good. It just makes being good the profitable strategy.

False Signals and Gaming the System

No system is perfect. Smart people will always look for ways to fake signals at lower cost. The college admissions scandal showed wealthy parents buying test scores and athletic credentials. Fake online reviews plague e-commerce.

The arms race between signals and fakes never ends. Each time a signal becomes valuable, incentive grows to fake it. This gradually undermines the signal’s credibility until a new, harder to fake signal emerges.

Blockchain advocates argue this is why decentralized verification matters. Can’t fake the blockchain. But even that has limitations. You can verify the transaction happened. You can’t verify that the transaction meant what someone claims it meant.

The general principle holds though. The harder a signal is to fake, the more credible it remains. This is why physical demonstrations beat testimonials. Why portfolios beat resumes. Why trial periods beat interviews.

Applying the Theory

What does this mean practically? Stop telling people what you are. Show them in ways that would be hard to fake.

Want to demonstrate reliability? Don’t say you always follow through. Build a track record others can verify. The ten years of showing up matters more than the promise to keep showing up.

Want to prove expertise? Don’t list your qualifications. Solve problems publicly where everyone can see the quality of your solution. The contribution speaks louder than the credentials.

Want to establish trustworthiness? Don’t ask people to trust you. Give hostages to fortune. Make commitments that cost you dearly if broken.

The pattern repeats across domains. Actions that cost you something, especially if they would cost someone without the quality even more, are credible. Words are not.

This might seem cynical. It’s actually liberating. You don’t need to convince anyone of anything. You just need to act in ways that reveal the truth about yourself. The signaling takes care of itself.

The Long Game

Building credibility through costly signals takes time. There’s no shortcut. This frustrates people who want quick results. But the time itself is part of what makes it work.

Anyone can maintain a facade briefly. Keeping it up for years is different. The person who blogs consistently about software engineering for five years probably knows software engineering. The faking costs would be prohibitive.

The business that has operated honestly for a decade probably won’t suddenly scam you. They’ve invested too much in their reputation. Patience becomes a competitive advantage. Most people won’t do hard things consistently over long periods. Those who will automatically separate themselves from the pack.

This also means your past constrains your present. Every choice is a signal that future observers will interpret. The person who job hopped five times in three years signals something different than the person who stayed at one company for a decade. Neither is necessarily better, but they signal different qualities.

Your history is your most costly signal because you can’t change it. This makes it your most credible one.

The Quiet Truth

The most powerful signals are often silent. They don’t announce themselves. They just exist, waiting to be discovered.

The best developers don’t have “rockstar” in their Twitter bio. They have GitHub profiles showing thousands of contributions. The most successful investors don’t brag about their returns. Their funds are closed to new investors because they’re oversubscribed. The real experts don’t tell you they’re experts. They just answer questions correctly and move on.

This creates a strange world where the people broadcasting their qualities most loudly are often the least qualified. And those with real qualities often seem humble or even invisible. The signal and the noise have inverted.

Learning to distinguish them might be the most valuable skill in an age of infinite cheap talk. Let others waste energy on persuasion. You can focus on reality instead.

The game theory of credibility isn’t really about games at all. It’s about aligning what you claim with what you can prove through actions that speak louder than words ever could.